What New York Does Right: Street Layout

I’ll admit it. Coming back to New York after a week on the coast of South Florida in March can be a little bit of a downer. According to my roommate’s trusty Game of Thrones weather app, on a three hour flight I went from Pentos to Winterfell. Sadly, beaches here will never compare with Miami’s South Beach, and neither palm trees nor mangroves will ever bloom in Central Park.

But with my feet firmly on New York concrete and a $2 slice of excellent pizza in my hand, the regret faded away. I’ve driven from New York to Seattle and back, and been all over the east and west coast (thanks to med school interviews). Despite what I’ve seen, there is a reason so many Americans, particularly young people, want to live in the city. New York gets so many things right, and these things are so entwined with the culture of this place that even if I leave for a bit, I know that they will be here for me when I get back, and that is the best comfort a home can offer. Here lies what New Yorkers can be proud to call their own, from birth to death. I’ll tackle one topic per post. Let’s start with what binds the whole city together: the streets.

History

By the miraculous circumstance of three historical forces: the Commissioner’s Plan of 1811, the design of Central Park by Frederick Law Olmstead, and the battle between Robert Moses and Jane Jacobs over the adaptation of the city to the automobile, Manhattan has evolved into one of the most fantastic urban landscapes to be traversed by cars, pedestrians, and bikers alike. Nowhere else in America will you find two-thousand-odd blocks of dense cityscape unbroken by the scars of massive highways.

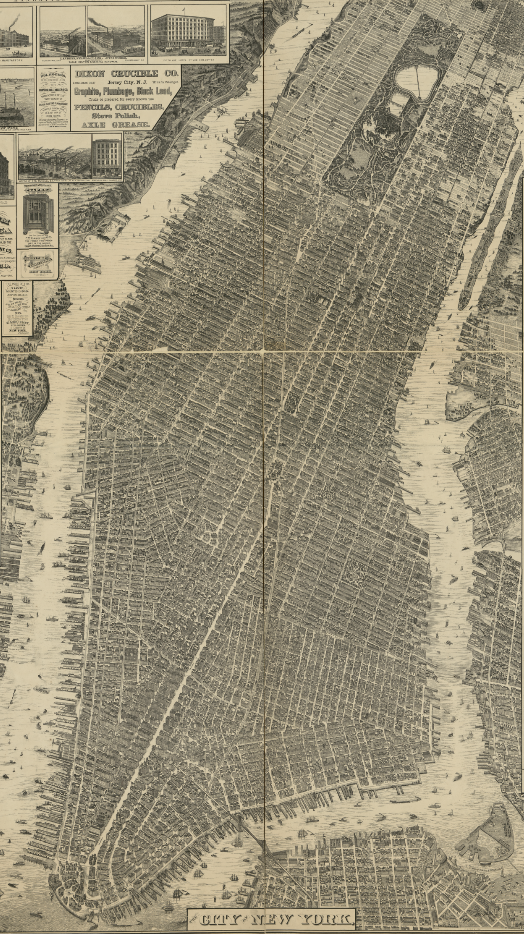

The Taylor map, 1879.1 The street layout seen here is practically identical to what we have today in 2013. The even “grid” starting at Houston is noticeable.

The Taylor map, 1879.1 The street layout seen here is practically identical to what we have today in 2013. The even “grid” starting at Houston is noticeable.

The result is astonishing in scope and is, at once, delightfully rational and historical. Above Houston St. (the effective extent of the city before the Commissioner’s plan), a mostly regular grid of narrow streets and wide avenues reigns, where one can think of a location—say, “Fifty-first and eighth”2—and immediately grasp the distance to it as well as the most likely routes. Below Houston St., a cobweb of competing street orientations must be learned, but therein lies sparkling neighborhoods and cultures that can be discovered and rediscovered over a lifetime. Because the grid expanded north as the city grew3 (to 21st St by 1834, and 57th St by 1844) and the central business district shifted from Lower Manhattan to Midtown as the main industries of the city evolved, the centrality of the street grid also coincides with the area of greatest commercial density, unlike cities with less room to grow (e.g., Boston).

Comparison

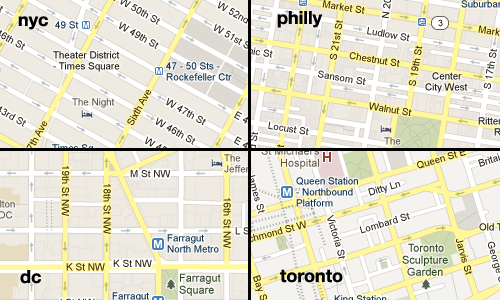

You might protest: “Oh, but many other great American cities use a grid layout.” None get it quite as perfect, however. Let’s use the following comparison, taken with all maps at the same scale, to start the discussion:

Imagery from Google Maps.

Imagery from Google Maps.

Two questions as should arise as you compare these: Which is the easiest for the motorist and pedestrian to navigate? Which creates the most pleasing city environment? A number of things can disrupt a street grid plan:

-

Too many irregularities. Philadelphia was one of the first cities in North America to use a grid system, but it did not enforce it as rigorously as New York; therefore, every block encountered is a potential surprise, and the order of the east-west street names must be memorized. This applies double to Toronto, because none of the streets are named predictably, and exceptions abound.

-

No contrast between streets and avenues. DC was more rigorous in sticking to the grid, but the blocks are too squarish. The result is there is no rhythm between commercial “edges” facing the avenues and residential “meat” on the interior of each block, as there is in New York, allowing better mixed use of every block—even in high density zones, many blocks can accomodate smaller townhouses and walk-up buildings within their interior4. Having uniformly wide roads also fails to concentrate traffic along one axis. Because avenues are wider and farther apart in the Commissioner’s Plan, north-south travel is more busy but also more efficient (this also happens to be the long axis of Manhattan, and thus the one more traversed). This avenue layout creates traffic, visibility, and natural congregation points within each neighborhood for street-level commerce. Such traffic can be tolerated only because there aren’t…

-

Too many two-way roads. Toronto is a terrible offender here. While motorists might think that two-way roads simplify route calculations, the reality is that they completely snarl traffic during high demand periods. Turning is the most expensive operation for traffic at an intersection, as cars have to cross through either other cars (with left turns) and possibly pedestrians in the crosswalk to clear the box. Until they can do that, cars in the lane behind them cannot move. At an intersection of two-way roads where all turns and pedestrian crossings are allowed, four lanes per road are going to be jammed for every green light without some special accomodation: separate left turn/right turn lanes and signals, which cost space and time per signal change, or randomly disallowing left or right turns, which destroys any claimed advantages in navigability.

In New York, the average intersection is two unidirectional streets, causing no crossing of car paths and only one possible turning direction. Combined with the Barnes Dance to clear crowded intersections of pedestrians, and synchronized green lights (called a “green wave”) down major arteries, one can typically drive 50 blocks north or south on a large artery without hitting a red light. There is also a nearly regular alternation of north/south and east/west travel, with changes in directionality made very rarely throughout the grid. The result: a graceful compromise between pedestrian and automobile friendliness.

Get on 3rd Avenue in the center lane and you will practically fly uptown. Taken from Google Street View.

Get on 3rd Avenue in the center lane and you will practically fly uptown. Taken from Google Street View. -

Streetcars and elevated trains. Driving among streetcars that occupy center lanes shared with cars is supremely frustrating. Not only is there a mad dash to slip around them between intersections, but every time the streetcars stop, all other lanes must stop as well to avoid harming entering and discharged passengers. This happens to be precisely the system that Toronto employs in its central business district. Elevated trains remove the traffic issues, but pollute thunderous noise, block out sunlight at the street level, and create an intimidating row of pillars for motorists to dodge. Sorry Chicago, your ‘L’ train may hold some quaint charm and makes for a cool scene in The Dark Knight, but Manhattan made life so much better by sinking most trains underground.

There are two more things that really kill street grids. They are probably best explained pictorially, since they would have been too unfair to show in the tiny representative samples I chose above. Here’s the first offender, seen across the street from where I lived in Toronto.

Hey, it’s the CN tower over there! Should be an enjoyable five-block walk from here. Oh, wait. Taken from Google Street View.

Hey, it’s the CN tower over there! Should be an enjoyable five-block walk from here. Oh, wait. Taken from Google Street View.

This is not an angle of the CN tower often advertised in Toronto tourism material. Railway lines through a downtown core? Unsightly, loud, and difficult to cross, they are an impenetrable wall for pedestrians and bikers, which is a shame, because those brand new lakefront condos are aching to be connected to the rest of the city. Once railways are buried, as in the Park Avenue tunnel or the East River tunnels under 32nd and 33rd St. (both operational and electrified by 1910!), the street level can be pleasant again5. Here’s another neighborhood destroyer, in Philadelphia:

Hey, it’s downtown Philadelphia over there! Should be an enjoyable five-block walk from here. Oh, wait. Taken from Google Street View.

Hey, it’s downtown Philadelphia over there! Should be an enjoyable five-block walk from here. Oh, wait. Taken from Google Street View.

Expressways can likewise destroy the walkability and street atmosphere of a neighborhood. Take for instance the South Bronx, fully wrapped and skewered by interstates. Fortunately, most of Manhattan avoided a similar fate thanks to Jane Jacobs and other militant conservationists, who successfully fought off a Lower Manhattan Expressway that would have destroyed Soho and Little Italy (two of New York’s most vibrant neighborhoods today) and a Mid-Manhattan Expressway which, even more insanely, would have leveled some of the most expensive commercial real estate in the world and driven highways through the middle of skyscrapers6.

The division and congestion created by a highway is expensive and difficult to remedy. Just look at Boston, which opened a Central Artery straight through downtown in the 1950’s only to see it clog up with cars and decrease access to historical and cultural neighborhoods like the North End from downtown. The problem was recognized by 1982, with construction on the infamous “Big Dig” to bury the expressway underground taking sixteen years and costing an estimated $22 billion, several investigations, and one death7. The result is obviously much more pedestrian friendly, and the surrounding neighborhoods may eventually heal together with enough creative landscaping, but it came at an enormous price.

This used to be a expressway in Boston. Moving it underground was the most expensive US highway project to date. Taken from Google Street View.

This used to be a expressway in Boston. Moving it underground was the most expensive US highway project to date. Taken from Google Street View.

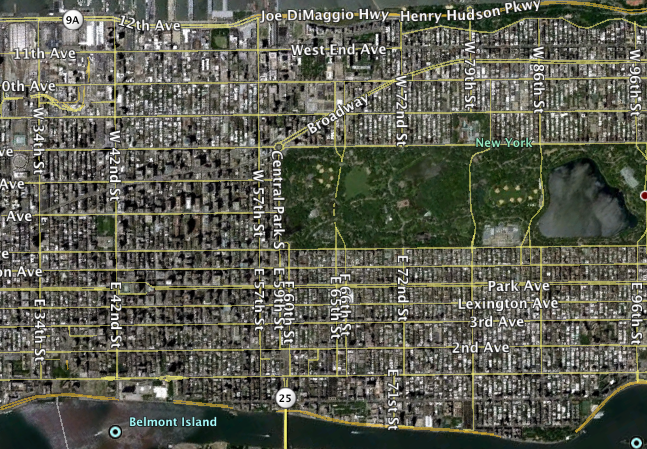

This is not to say that highways are completely unimportant; Robert Moses dutifully ensured that Manhattan had limited-access north/south arteries along the East and Hudson rivers. And they can be used, for instance, to zip from City Hall to the Apollo in 20 minutes during off-peak hours, a trip spanning most of the island. But their disruption to pedestrians is constrained to the margins, leaving the city inbetween magnificently unblemished. From Avenue D to West End Ave, a pedestrian will be hard-pressed to find more than six lanes of traffic between him and the other end of a crosswalk.

Blocks on blocks on blocks. Imagery from Google Earth.

Blocks on blocks on blocks. Imagery from Google Earth.

Continuity of neighborhoods

Here’s a maxim that could probably be proven using New York as a test case: the natural limit of neighborhood continuity across pavement is somewhere around six lanes. It’s a distance where you can still recognize your friend in front of a store on the other side of the avenue and jog over to her when traffic slows. Unlike, say, the twelve-lane death trap that some call Queens Boulevard8, you could get comfortable with your grandmother crossing a Manhattan avenue by herself. Anything just over six, e.g., by replacing two lanes with streetcar tracks on Spadina Ave in Toronto, and you start feeling noticeably less happy about crossing it every day. Let’s recall that six lanes are more than sufficient for fast travel in one direction—refer to that picture of 3rd Avenue above, which has five, giving you one center lane, a passing lane on either side, and outer lanes, which can accommodate the cars turning, parking, and performing general shenanigans without slowing down thru traffic.

On the other hand, there is also a reasonable minimum for street width. New York’s is generally a central quasi-double lane with parking on both sides of the street. Observe the following comparison between typical streets in New York and Philadelphia.

E 70th in NYC vs. S 12th in Philly. Both images courtesy of Google Street View.

E 70th in NYC vs. S 12th in Philly. Both images courtesy of Google Street View.

In New York, residents can park on both sides of most streets, and traffic flows down the large center lane. If somebody double-parks to unload a passenger or perform some shenanigans, as this minivan has done in the picture (it is a fact of American city traffic that vehicles will selfishly stop to occupy any point along a streetside), no matter: there is still enough room for cars to squeeze past, as the yellow taxi is doing. In Philadelphia, one whole side of the street is typically wasted. Why? It’s the awkward width of the street: if there were parked cars on both sides, somebody stopping to unload or perform shenanigans, as these construction guys are doing, would be impeding all movement. The center lane of this street has insufficient “wiggle room” and thus a whole edge must be lost to bare curbside that becomes the de facto “shenanigans” lane. Philly should try to repurpose some of this awkward space to make more bike lanes. (Also, what’s the deal with the abandoned trolley tracks in the center of the street, perfectly positioned to provoke anxiety in motorists and tip over passing cyclists?)

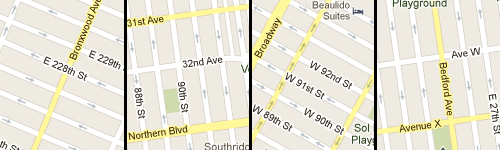

There is no way the Commissioner’s Plan could have predicted that 60 feet would be the perfect width for three cars with squeeze room for one more and two sidewalks on either side, but it works so well that it makes you wonder if New York streets didn’t unintentionally influence the standard 12 foot lane width for automobile traffic or the width of cars in general. Other cities that contend with comparable urban density in America can only wish they had evolved with such a fortuitous configuration9. As the outer boroughs of New York largely perpetuated the spread of the rectangular block style and street widths of Manhattan, the city has a remarkable uniformity to its street texture, from Coney Island Ave all the way to E 233rd St in the Bronx, with each block theoretically capable of the same eventual mixed residential and commercial density as a block in Midtown.

From left to right, the Bronx, Queens, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Each tile is at the same scale. Imagery from Google Maps.

From left to right, the Bronx, Queens, Manhattan, and Brooklyn. Each tile is at the same scale. Imagery from Google Maps.

Streets aren’t just for cars

So far I’ve argued mostly on the premise that streets should be built for pedestrians as well as for cars. To anyone in New York, where just as many walk and use public transit to get to work as drive, this seems blatantly obvious. Many studies indicate, as should common sense, that supporting only a car-commuter culture will negatively affect public health. Having trudged around the dismal central business districts of Worcester, New Haven, Hartford, Springfield, Sioux Falls, Detroit and so many other American cities that seem to have given up on attracting pedestrians, it’s clear that any street life that would inspire young workers and businesses to come and explore has been lost. All of these places seem to have the same vacant storefronts surrounded by massive buildings and parking structures. How free can one feel in a city where it seems safer to stay in the car? What’s the psychological effect of being chronically tethered to a two-ton hunk of aluminum and steel?

Let’s not forget the bicyclists, either. Say what you will about Mayor Bloomberg, but watching this map grow and exploring its fringes over the past decade has transformed how I feel about and move around the city. You can now bike from Westchester County to Jacob Riis Park mostly along reserved bike lanes, some of them separated from auto traffic10. I’m planning some posts about some of the nice longer trips that can be made into the Palisades, the South County Trail, and others. The bike lane effort has been a stunning accomplishment for the DOT and I only hope that they’re here to stay after the mayor leaves.

Coming next

Alright, I’ve said my piece and that wraps this first part of a (possibly never-ending) series on things New York gets right. Stay tuned for articles planned on, but not limited to: pizza, subways, taxis, skylines, street food, bagels and lox… need I go on?

This post used the word “shenanigans” a total of five times.

Did I get something wrong? You can flame me on Reddit.

-

Codex 99, a bottomless blog on the history of the visual arts and graphic design, has a fantastic review on the evolution of three-dimensional cartography depicting New York. ↩

-

This is the correct way to say a Manhattan address, with street name before avenue. If you’re cabbing to the East Village, don’t mess this up. It’s in the rules. Technically only two blocks exist where this could be ambiguous, but still. If you clicked that link, you may have noticed Google gets it wrong. Google is not a New Yorker. ↩

-

The Times hosts an interactive map showing the order in which Manhattan streets opened. ↩

-

In crowded commercial districts like Midtown, you might find this situation inverted—sometimes with goofy results—but the streetfront is usually so continuous that it can be hard to notice! ↩

-

Boston had a rail line through the South End and Back Bay sunk into a tunnel in preparation for the construction of a new highway, but resistance was so fierce following the Central artery disaster that it was abandoned. Decades later, it was repurposed into one of a neat linear park that connects the surrounding neighborhoods. ↩

-

The idea was to facilitate movement between Long Island and Jersey, although why this had to occur through the most crowded and expensive part of Manhattan was an objection that thankfully was never overcome. The only expressway of this category, the Trans-Manhattan Expressway, has become a continually-clogged pinchpoint for interstate trucking and travellers, with less than ideal consequences for local residents. The Mid-Manhattan Expressway project did inspire some impressive “futurism”-laden design illustrations, though. ↩

-

12 tons of concrete ceiling panels in a tunnel collapsed, crushing a car and killing one of its passengers. This resulted in criminal charges and a review of Boston’s entire highway system. ↩

-

I’m not kidding about it being dangerous. In the 90’s an average of 10 people were killed per year trying to cross Queens Boulevard, earning it the name The Boulevard of Death and the installation of cheerful signs proclaiming A pedestrian was killed crossing here. ↩

-

A rather fun counterpoint to this article is a critique of the Commissioner’s Plan apparently written in the 1930’s, which marveled that a city of 85,000 could have laid itself out in preparation for millions of residents, but proposes that more avenues and diagonal arteries should have been included, and less cross streets. From the standpoint of 2013, I’m not sure I agree. Broadway creates confusing and crowded 6-way intersections wherever it crosses an avenue, and its controversial replacement with a pedestrian plaza in Times Square has actually improved safety and traffic in that area. ↩

-

They aren’t always respected: as this short video tracing the bike lane on W 106th St. shows, many cars and UPS men will use the lane as an excuse for more shenanigans. But the occasional intrusions aside, is this not a glorious way to move about a city? ↩

Discuss this post on HN.